When the First World War began in 1914, eager volunteers rushed to join the newly raised Pals battalions of their local Regiment. But this meant that when a Pals battalion suffered heavily in battle, as on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, whole communities went into mourning. This mistake was not repeated in the Second World War. And so, in 1942, Jack Fairweather, a twenty-one-year-old London-born cabinet maker, found himself serving as a gunner in County Durham’s 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery.

After meeting his future wife at a dance in 1943, Jack Fairweather began to write to her, until, by the time he left the Army in 1946, he had written her 376 letters. These letters survived and in March 2022 Jack and Irene’s son, Stephen, presented a bound transcript of his father’s letters to Durham County Record Office.

Amongst those letters were five written in 1945, when the young soldiers of the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment came face to face with the horrific reality of Belsen Concentration Camp.

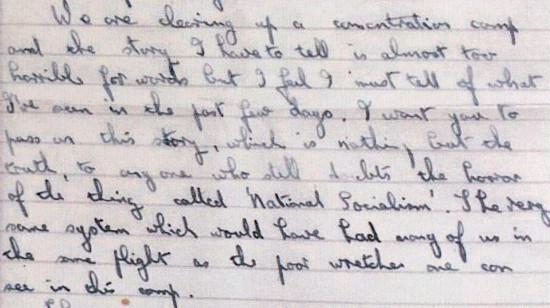

And in his first letter from Belsen written on 23rd April 1945, Jack told Irene:

We are clearing up a concentration camp and the story I have to tell is almost too horrible for words but I feel I must tell of what I’ve seen in the last few days. I want you to pass on this story, which is nothing but the truth, to anyone who still doubts the horror of the thing called ‘National Socialism’. The very same system which would have had many of us in the same plight as the poor wretches one can see in this camp.

This online exhibition will tell the story of these Durham gunners at Belsen in 1945. But we must begin with the story of the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery.

Before the First World War, there were five Territorial battalions of The Durham Light Infantry in County Durham. By the late-1930s, however, the growing threat of Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe (air force) led to a rapid expansion of Britain’s home defences and changes for two of those DLI battalions. One of these changes eventually saw the formation in West Hartlepool of the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the Royal Artillery. And it was this Regiment that Jack Fairweather joined in 1942.

The 113th Regiment, armed with Swedish-designed Bofors guns firing explosive shells two miles high, first joined southern England’s anti-aircraft defences, but in early 1943 began to train for a new role as a mobile anti-aircraft regiment. Because, whenever the invasion of Europe came, the 113th Regiment would be part of that invasion.

In the weeks following D-Day (6th June 1944), the Allies poured men and equipment into France, including the 113th Regiment. The fighting was intense during the battle for Normandy, and the Regiment shot down 20 enemy aircraft.

Following the breakout from Normandy, the 113th Regiment joined the rapid advance across France and Belgium, and into Holland. By the end of March 1945, however, with the Allied armies across the river Rhine and the Luftwaffe all but finished, new tasks were found for the British Army’s anti-aircraft regiments. The gunners of the 113th, however, could never have imagined the extraordinary task that they were about to be given.

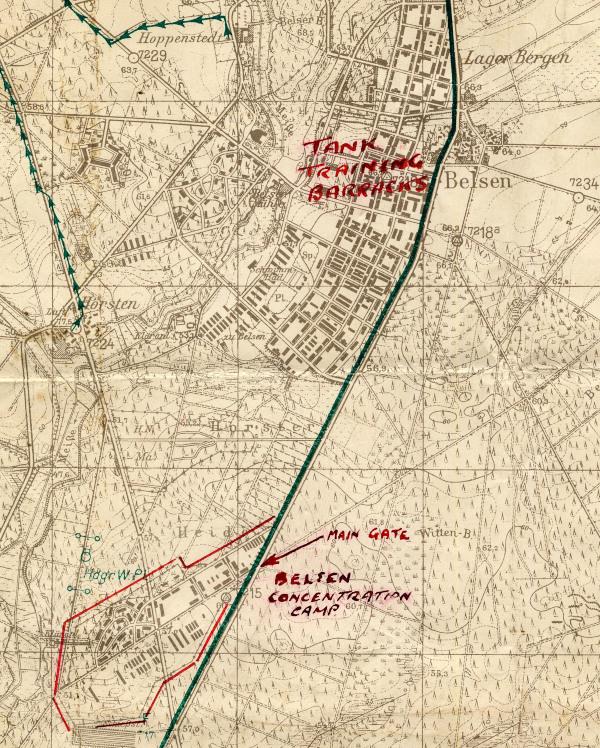

On 12th April 1945, as the British 2nd Army was advancing into Germany, senior German Army officers asked for a truce to stop the fighting around a camp near the village of Belsen, where typhus was raging out of control. This highly contagious disease, spread by lice, could kill in two weeks if left untreated.

A truce was agreed and on 15th April the first British soldiers arrived at the concentration camp. And there they found hell on earth with heaps of unburied corpses, and thousands of starving, diseased, barely alive, men, women, and children crammed into wooden huts. There was no clean water, no sanitation, no electricity, and no food, not even the thin soup made from turnip and potato peelings that had been the prisoners’ usual diet.

Belsen, however, was not an extermination camp. There were no gas chambers, but disease, starvation, deliberate neglect, and inhuman brutality killed just as certainly as the gas chambers.

Over 120,000 people were imprisoned in Belsen concentration camp during the war. Of these, at least 52,000 died. Most in the final chaotic months of the war. Not all the camp’s victims, however, were Jews. There were also thousands of non-Jews sent there from across Europe, including political prisoners, homosexuals, Roma, and Poles captured after the collapse of the Warsaw Uprising in early October 1944. And 9,000 of these Polish prisoners were women and girls.

Inspecting the camp late on 15th April, a senior British Army officer estimated that there were 28,000 females and 12,000 males alive in the camp. Most in need of immediate hospital treatment. He also estimated that at least 10,000 of these people were still going to die, regardless of what the Army’s medical services could do for them. And he also counted more than 10,000 unburied bodies abandoned in the overcrowded huts or piled in heaps about the camp and in the woods beyond.

By the end of the next day, 16th April, British soldiers had taken full control of the camp, though not before an unknown number of the hated Kapo had been killed. These were prisoners, who, in return for a few privileges from the SS guards (Schutzstaffel), had acted as brutal overseers in the camp.

Meanwhile, as the British Army was bringing the first clean water, food, and medical services to the camp, the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment was on the road to Belsen.

With the gunners were drivers and mechanics from the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), signallers from the Royal Corps of Signals, and a mobile workshop of the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers (REME). These specialists were to prove their worth over the next few weeks.

Passing warning signs painted in red – ‘Keep Out’ and ‘Danger Typhus’, the convoy stopped outside Belsen concentration camp on 18th April. The gunners set up their tents, had a meal and slept. And the next day they took over from soldiers who had been at the camp since 15th April.

On 23rd April, Gunner Jack Fairweather wrote a fourteen-page letter to his future wife describing those first few, unforgettable, days at Belsen: the horrific sights he witnessed, the piles of dead, and above all the smell of death and decay that hung over the whole camp:

We were informed beforehand what to expect, but even though I kept pictures in my mind of atrocities which I’d seen in the newspapers I was more than shocked by the sights that met my eyes. I hope you never see such things but it would do many doubters good to feast their eyes on what we have seen. I myself have read about such camps and seen pictures in the papers or the films, but all that and seeing for one’s self is an entirely different thing. I say seeing but perhaps smelling is worse…

The camp area isn’t so very big but at one time it held sixty thousand people but now there are about thirty thousand and they are still dying at the rate of 600 a day. Of course no one knows the exact number and even yet the place is all upside down…

As one walks through the camp one can see dead lying everywhere, some in piles dozens high, others by themselves, and every now and then one more drops…

No words of mine can aptly describe the conditions here.

During the Second World War, British soldiers were forbidden to say in their letters where they were or what they were doing, but at Belsen censorship was dropped and the soldiers were positively encouraged to tell the people back home about what Jack Fairweather called “the truth of things”.

When Jack wrote this first letter, his Regiment was in charge of clearing the piles of corpses. Vital work to stop the spread of disease. Some seventy SS guards – men and women – who had been taken prisoner when the camp was liberated, did the grim work, collecting the bodies, loading them onto German Army lorries, and then unloading them into the mass graves dug by bulldozers. All under the watchful eyes of the 113th Regiment’s armed guards.

At night these SS prisoners were locked in cells guarded by the gunners. Some twenty of the SS prisoners died within a few weeks of the camp’s liberation. Two killed themselves, some were shot dead trying to escape, but typhus was the main killer.

Day after day the dead were buried and by 25th April the camp was clear. After the mass graves had been covered with soil, funeral services were read, and notice boards set up recording the date and, if known, the number of dead in the grave.

![Signboard marking Grave No. 9, Belsen concentration camp, May 1945. Text reads: Grave No. 9, No. [Number] Unknown. Image © Durham Record Office (D/DLI 7/404/64)](https://durhamrecordoffice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/d_dli0007_0404_0064.jpg)

Not every survivor, however, was able to walk to one of the make-shift canteens for a bowl of soup or stew. Those too ill with typhus or dysentery lay in the huts unable to help themselves and unable to digest the food offered to them. And it was not until some 100 medical students – all volunteers – arrived at the end of April from teaching hospitals in London that the suffering of these people was eased. Even so, at least 14,000 people died after Belsen’s liberation. Even more than had been grimly predicted during the first inspection of the camp on 15th April.

The specialist soldiers with the 113th Regiment also had a major impact on the camp. The RASC’s drivers collected food and supplies, whilst REME’s electricians and fitters restored the camp’s electricity, repaired the camp’s own bakery, and seized fire engines from a nearby German town to pump water from a river into the camp for the cookhouses and the shower blocks.

As the camp was cleared with the dead buried and the survivors fed, de-loused, washed, re-clothed and moved out of the camp to prepared hospital or reception areas, so the 113th’s gunners undertook new – more pleasant – duties, including making wooden cots for a children’s ward, and swings and see-saws for a playground.

The 113th Regiment had arrived at Belsen on 18th April 1945, as Nazi Germany was collapsing in flames. Within three weeks, as the gunners laboured in the camp to help the living and bury the dead, Hitler had killed himself, Berlin had surrendered to the Red Army, and the war in Europe was over. Tuesday 8th May 1945 was proclaimed as VE Day – Victory in Europe Day. And the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, having seen at first hand the horrors of Nazi Germany, did not let the day go unmarked.

That evening, after parading outside the camp with their vehicles and guns, past senior British, Soviet and US officers, plus a company of freed Russian prisoners of war, the Regiment fired a Victory salute. The next day, the gunners were back at their duties in and out of the camp.

In Jack Fairweather’s letter to ‘My Darling Renee’, dated 10th May, he described his VE Day:

Well darling VE day is over although to us it was much the same as any other day. We were up just as early in the morning and those of us who weren’t on duty in the camp spent the morning cleaning guns, tractors, jeeps and motor cycles for a victory parade at six o’clock in the evening. For this parade we rode through the SS barracks, where most of the inmates from the concentration camp are now recovering and past a saluting base. The brigade commander took the salute as the regiment went by and he had a company of Russian ex-prisoners with him at the saluting base. Anyway we went around the camp and then all our guns were formed up in a hollow square in the parade ground. For a victory salute, they each fired about thirty rounds and I think the inmates of the camp must have wondered what was happening…

Anyhow, the CO [Commanding Officer] gave the official cease fire and that was our victory day. For the rest of the day I just laid down on my bed to dream of my leave and you, especially you. Some of the boys got drunk on wine and champagne found in German houses, but I wasn’t interested, believe it or not. I was in bed by nine o’clock but sleep was impossible with the noise of gunfire all night long.

On 19th May, the last of Belsen’s huts was emptied of the living and the dead and, supervised by the 113th Regiment, the camp was burnt to destroy the last traces of disease. Two days later, after a brief ceremony, and watched by cameras, and an audience of liberators and survivors, flamethrowers burnt the last wooden hut to the ground.

Alexander Allan, one of 113th Regiment’s officers at Belsen, was interviewed by the Imperial War Museum in 1991. And he remembered the burning of the huts:

It was on the 21st of May… flame throwers set alight to all the huts, which were now deserted and empty except for a few skeletons I suppose you may say and full of human rags and excreta and all the rest of it. And all those camps, all the huts within the wire were set on fire one by one and they went up in great plume of horrible – it was all so wonderful really – smoke and flame.

You can listen to the interview with Alexander Allan on the Imperial War Museum’s website.

Jack Fairweather, however, did not witness this climax to the liberation of Belsen concentration camp. Granted home leave, he left the camp on 16th May, never to return.

The 113th Regiment, however, still had some work to do and this included painting two large signs in English and German at the camp’s entrance marking the site of ‘The Infamous Belsen Concentration Camp’.

‘This is the site of the Infamous Belsen Concentration Camp

Liberated by the British on 15 April 1945.

10,000 unburied dead were found here.

Another 13,000 have since died.

All of them victims of the

German New Order in Europe

and an example of Nazi Kultur’.

At last, on 24th May 1945, the 113th Regiment packed up its vehicles and left Belsen for Hamburg. There it spent the night, and there the commander of the British 2nd Army thanked the Regiment for all it had achieved at Belsen.

The 113th’s gunners then drove without their anti-aircraft guns, but with 6,000 bottles of beer, to the Baltic coast for 10 days’ well-deserved leave. After their seaside holiday, the 113th’s gunners spent several months on occupation duties in Germany, before the Regiment was disbanded in November 1945, and the gunners returned to their families, homes, and jobs.

Probably, few of the men of the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment ever forgot the weeks they spent at Belsen concentration camp in April and May 1945. And how could they forget what they had seen and heard and smelt amid all that death and suffering?

Jack Fairweather knew that he would never forget, writing to his future wife in his first letter from Belsen:

The last few days have been like a dream to me, or should I say a horrible nightmare, but I’ve seen things that will be on my mind for the rest of my life.

One young gunner, James Illingworth, was filmed by a British Army cameraman inside the camp on 24th April 1945. Barely able to control his anger, he says that, after seeing the camp which is “beyond describing”, he clearly knows what he is fighting for.

You can see this film on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website.

Warning: this film contains horrific images of Belsen concentration camp.

And those memories did not fade with time. Speaking to an Imperial War Museum interviewer in 1991, Alexander Allan had clearly not forgotten what he had witnessed inside the camp almost 50 years before:

Well, the only way really to describe it is the fact that there just was a carpet of human bodies. Mostly very emaciated, many of them unclothed, jumbled together.

People had just died where they stood. And they were outside and inside, of course, the various huts. But they were outside, you know, lying where there were trees or any open ground.

It just went on, it was incredible.

The bodies didn’t putrefy because they were so skeletal. There was so little flesh on them. Their arms and their legs were just like matchsticks really.

But it was a gruesome, horrible sight, and never again, never.

As well as Jack Fairweather’s letters and Alexander Allan’s interview, an important collection of photographs, letters and news cuttings kept by Stanley Levitt and given to the DLI Museum after his death in 1977 was used to put together this exhibition.

Born in Hartlepool in 1919, Stanley Levitt joined the Territorial Army before the Second World War and was, with the rank of Battery Sergeant Major, in charge of one of the 113th Regiment’s three gun batteries at Belsen. In the above photographs that’s BSM Stanley Levitt standing with his arms on his hips in front the Belsen notice board and sitting at the front of the boat.

Amongst Stanley’s collection was a copy of ‘The Story of Belsen’. This booklet, packed with facts and photographs, was written by one of the 113th’s officers and printed in Germany before the Regiment left for home. On the front of this booklet is the blue shield badge of the British 2nd Army, which was worn as an arm badge by the 113th’s gunners.

This online exhibition began with Jack Fairweather’s first letter from Belsen written on 23rd April 1945 and will end with that letter’s final heartfelt plea. A sentiment, no doubt, echoed across the 113th Regiment:

I’ve had enough of hell, and I just want you and a little bit of heaven to keep me going.