After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Korea, which had been part of the Japanese Empire, was divided between Soviet Russia and the United States of America. Each created a new country in its own likeness and, from the start, communist North Korea and anti-communist South Korea claimed the whole country as its own.

On 25 June 1950 the North Korean People’s Army launched a full-scale invasion across the border. Within weeks, US soldiers were sent to support the South, driving the invaders back. In November 1950, as US troops advanced towards the Chinese border, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army intervened. Before a truce ended the fighting on 27 July 1953, over three million people, most Korean civilians, had been killed and much of the land devastated.

After the United Nations (UN) condemned North Korea’s invasion, sixteen countries pledged to send troops to aid South Korea. Soldiers from Britain, Australia, Canada, India and New Zealand fought together as the 1st British Commonwealth Division.

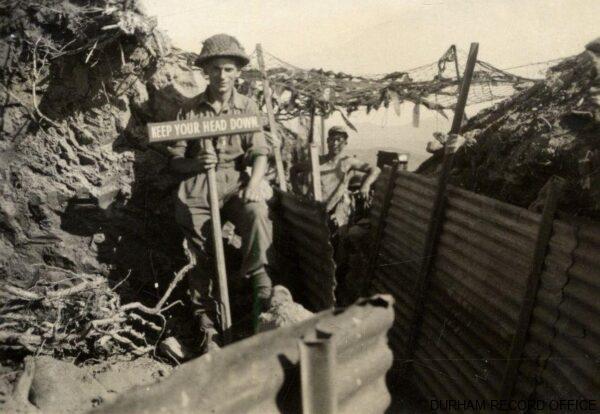

On 7 September 1952, the 1st Battalion The Durham Light Infantry (DLI) landed at Pusan [now known as Busan] in South Korea to join the Commonwealth Division. Peace talks to end the war had begun in July 1951, but the fighting did not stop, as both sides dug in along the border. In these trenches, the Durham soldiers learnt to live and fight, as their fathers had done on the Western Front during the First World War.

Most of these soldiers were young National Servicemen, called-up to serve two years in the Army, though many of their officers and sergeants were battle-hardened veterans of the Second World War.

This online exhibition will explore the experiences of these soldiers during the Korean War, through photographs and documents held by Durham Record Office; and through the memories of DLI veterans, Eric Burini, John Lightley and Allan Mavin, who served in Korea and who were interviewed in the 1990s for the Imperial War Museum. You can hear their voices on the IWM’s website:

- Burini, Eric Basil (Oral history)

- Lightley, John George Taylor (Oral history)

- Mavin, Allan Anthony (Oral history)

The first British troops had been sent to Korea from Hong Kong in August 1950. In 1952, it was the turn of the 1st Battalion DLI to join the battle, but before the battalion left Durham there was a special farewell service in the Cathedral, followed by a parade through the Market Place led by Lieutenant Colonel Peter Jeffreys, with the salute taken by Lord Lawson of Beamish, Lord Lieutenant of County Durham.

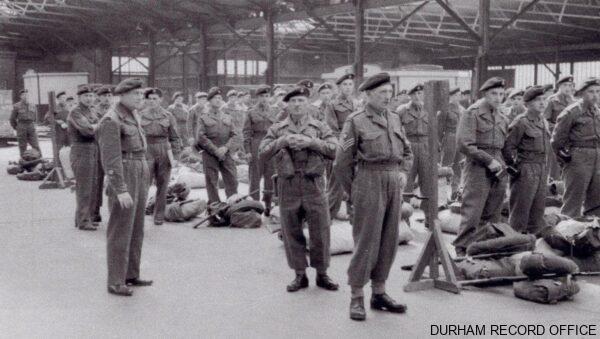

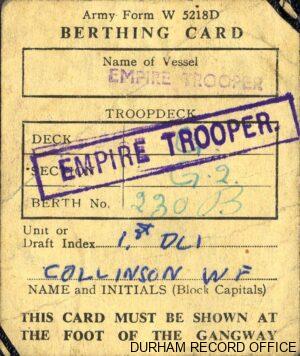

Before dawn on 28 July 1952, Brancepeth Camp, the DLI’s Depot [headquarters], was wide awake as the Durhams prepared for their move to Korea. After breakfast, the 800 soldiers collected their kit, rifles and other equipment and marched to Brancepeth station, where two special trains waited to take the battalion to Southampton and the troopship ‘Empire Trooper’.

Firm believers in the saying ‘The devil makes work for idle hands’, the DLI’s experienced officers and sergeants kept the young soldiers busy at sea with daily inspections, physical training, boxing, drill and live-firing. And the officers were also expected to keep themselves active and fit.

Finally on 8 September 1952, after stops at Aden, Ceylon [Siri Lanka], Singapore and Hong Kong, the Durhams landed at Pusan on the south-east coast of South Korea, where they were met by a US military band playing, to everyone’s amusement, the popular song ‘If we’d known you were coming, we’d have baked a cake’.

The DLI was, once again, off to war.

At Pusan, the battalion boarded a train for Britannia Camp, where the Durhams were to prepare for their first time in the Korean trenches.

A young officer, Second Lieutenant John Lightley, later remembered the two-day train journey:

We got into this appalling railway, the worst train you could possibly imagine, no lights, no windows, hard seats, no toilet – just a hole in the floor. We travelled for an hour then stopped for two hours, travelled for an hour, stopped for two hours. It was dreadful.

But there were compensations.

And some soldiers can always find ways to sleep.

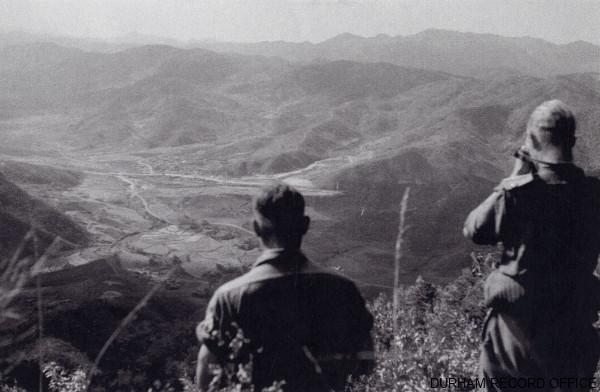

At Britannia Camp, the battalion lived in tents and trained hard for the front-line practising attack and defence, patrolling the steep hills by day and night, digging trenches, wiring, and live-firing all weapons. Finally on 24 September 1952, after first being driven in trucks across the Imjin River, the Durhams, led by an Australian guide, slipped, and stumbled on the rocky paths in the dark and driving rain to their trenches on the front line at Point 159. At dawn, the battalion got its first view across the valley to the Chinese-held hills opposite.

Shells and mortar bombs greeted the battalion and on 28 September Private William George from Stockton became the battalion’s first casualty, when he was wounded in the shoulder and evacuated to hospital. A heavier bombardment on 1 October killed Lance Corporal Edward O’Brien and wounded three others. Then, after ten days in the trenches, the battalion moved back to Britannia Camp for some relaxation and more training.

The Durhams returned to the front line on 1 November and set to work on what Australian soldiers called ‘trench beautification’.

On the forward slope facing the Chinese positions, and so at risk from direct shell fire or an enemy trench raid, communication trenches were dug six to eight feet deep, linking fire trenches and weapon pits. Sandbags were laid as carefully as bricks, and roofs supported by irons pickets and covered in rock and soil, with camouflage netting, barbed wire and mine fields completing the defences.

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Jeffreys believed that his battalion’s morale and fighting efficiency depended on the state of its defences and trenches, and so everything had to be just so. And the men themselves had to wash and shave and clean their boots and equipment every day, taking pride in themselves and their Regiment.

On the reverse slope, and so not in direct view of the Chinese positions but still at risk from shell and mortar fire, were the dug-outs or ‘hoochies’. This is where the soldiers lived.

General Sir Peter de la Billiere served with the 1st Battalion in Korea as a nineteen-year-old officer. In his book ‘Looking for Trouble. SAS to Gulf Command. The Autobiography’, published in 1994, he described life in the Korean trenches (page 65):

Like badgers, we lived in holes deep underground, and slept by day, emerging into the open under cover of darkness. Our main quarters were subterranean bunkers known as hoochies – substantial chambers quarried out of the hillside, with a minimum of five feet of overhead cover: earth and rock were filled back in on top of a ceiling of inter-laid steel pickets, so that they could withstand direct hits during artillery barrages. Since many of the Durham soldiers were miners, they could out-perform everyone else when it came to digging, and we prided ourselves that our earthworks were the finest in the line. In these hoochies we lived, slept, washed, shaved and ate.

Second Lieutenant John Lightley remembered something else that lived in the trenches alongside the Durham soldiers:

After the cold the most hated feature of our life was the rats, which infested the trenches. They were everywhere – in walls and roofs, communication trenches and undergrowth. One sergeant refused to sleep in his own hoochie alone in case they jumped on his face. They were found in sleeping bags and regularly ran across the table when you were eating. Most hoochies had leaking sandbag walls where attempts had been made to bayonet them. They were a serious health risk.

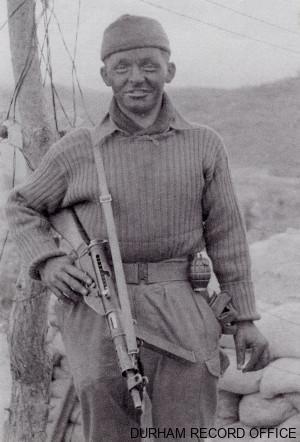

The Durhams, however, did not stay in their front-line trenches and hoochies. Every night, regardless of the weather, standing patrols of three or four soldiers with blacked faces took up positions in No Man’s Land to listen and watch and act as tripwires in case of a Chinese raid. At the same time, other fighting patrols of fifteen men led by a sergeant or a young officer moved down into the valley to listen for enemy patrols and, perhaps, spring an ambush catching an enemy patrol by surprise.

One early evening in June 1953, Captain Eric Burini with Corporal Moody left the battalion’s front line in heavy mist to take command of three fighting patrols. He later remembered:

We decided that the mist was useful cover to enable us to get out in daylight and find a really good lie up position. We were shortly joined by the three fighting patrols that were spaced out along two spurs on either side of us; and there we sat until it was nearly dawn. The main problem was keeping awake for that length of time… About an hour before dawn, we were ordered back to base, easier said than done, and the trickiest part of the operation. We were given heavy machine gun covering fire (more to cover our own noise than protective) and I got them all moving.

Night patrolling, however, was dangerous work, especially in the rain, ice and snow. There were casualties from enemy action and there were accidents. Just before dawn on 2 January 1953, Major Pat Donoghue and his patrol accidentally stumbled into a minefield in front of the battalion’s own trenches. He was killed and three soldiers wounded.

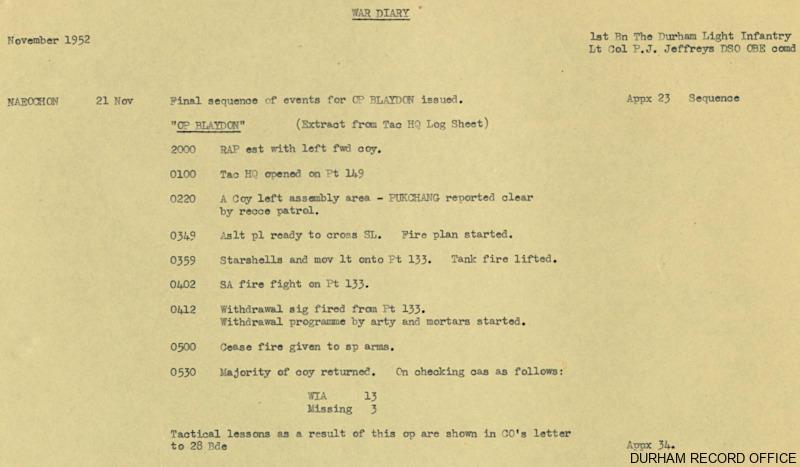

Early on 22 November 1952, the Durhams raided the Chinese trenches across the valley for the first time. This was Operation Blaydon, and its aim was to capture a prisoner, kill any resisting enemy soldiers and blow up the entrance to a tunnel dug into the hill. As the raiders from ‘A’ Company began to climb towards the Chinese trenches, however, they came under heavy fire, before the Chinese defenders withdrew into their underground bunkers. Under increasing Chinese artillery and mortar fire, the raiders returned to their own trenches, having failed to achieve their aim. Operation Blaydon cost the 1st Battalion DLI thirteen men wounded and three missing presumed dead. The casualties, however, would have been far worse had not all the raiders been wearing bullet-proof vests.

One of the wounded was Private Bryan Dolman, who later remembered:

When I was wounded, a blackness came over me. It was a strange feeling of calmness, which started in my legs, then came upwards. When I came to, there were explosions going on all around. Then Corporal Ronnie Moore appeared. He asked me if I could stand. I managed to stand on my right leg with great difficulty. He carried me a short way when he fell. I went rolling down the hill for a short distance, then he dragged me down to the bottom of the hill. He was saying all the time that I had to get back to Ann, my girlfriend, now my wife. When we reached the valley, he lifted me onto his back and carried me. We fell many times in the paddy fields. I lost consciousness a number of times. When we reached the small river in the valley, I stuck my head into the water and drank as much as I could. By then it was breaking daylight. We struggled on till we reached the bottom of our position, then Ronnie left me and went for assistance. A party came and dressed my left leg and right foot.

Bryan Dolman was soon in hospital in Japan and Ronnie Moore was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery.

WAR DIARY

November 1952

1st Bn The Durham Light Infantry

Lt Col P.J. Jeffreys DSO OBE commanding

NAECHON 21 November Final sequence of events for OPERATION BLAYDON issued.

‘OP BLAYDON’ (Extract from Tactical HQ Log Sheet)

2000 RAP (Regimental Aid Post) established with left forward company.

0100 Tactical HQ opened on Point 149.

0220 A Company left assembly area – PUKCHANG reported clear by recce patrol.

0349 Assault platoon ready to cross SL (Start Line). Fire plan started.

0359 Starshells and mov lt (move light – a searchlight) onto Point 133. Tank fire lifted.

0402 SA (Small Arms) fire fight on Point 133.

0412 Withdrawal signal fired from Point 133. Withdrawal programme by artillery and mortars started.

0500 Cease fire given to supporting arms.

0530 Majority of company returned. On checking casualties as follows:

WIA (wounded in action) 13

Missing 3

Tactical lessons as a result of this operation are shown in CO’s letter to 28 Brigade.

On 1 December 1952, in heavy snow and freezing temperatures, the 1st Battalion DLI left the front line for the reserve and work on the Kansas Line, a system of trenches that stretched across the Korean peninsula. As a break from the digging and wiring, the Durhams, after the failure of Operation Blaydon, practised night raids on an enemy-held hill to capture a prisoner.

Lance Corporal Allan Mavin remembered what he wore during the Korean winter:

You had a string vest, then an ordinary Army shirt and three pairs of Long Johns. The first pair, you had a slit up the front and the back, so you didn’t have to take them off for following the calls of nature. The second pair were of a woolly material, which were worn over the top of the first pair. Then you wore your trousers. You had a cap comforter over your head, like a little muffler, which you turned inside out, like the Commandos did during WW2. Big boots – exceptionally large. You had a thick inner-sole and thick stockings to keep your feet warm. You had a Parka, which came over your body to keep you warm. Two pairs of gloves: one pair of woollen gloves, the other were like gauntlets but only had a finger and a thumb like mittens. You hardly got them through the trigger guard of the rifle.

Still in reserve on Christmas Day 1952, the Durhams enjoyed a dinner of roast turkey and pork with all the trimmings, Christmas pudding with rum sauce, mince pies, nuts and sweets, plus bottles of free beer. Each man also received a parcel from the Mayor of Durham’s Korea Fund. These parcels, packed and posted from Durham in October, each contained two pairs of socks, two handkerchiefs, needles and thread, buttons, writing paper and envelopes, and packets of sweets.

Following a request from Colonel Jeffreys, the Korea Fund also sent portable radios to the 1st Battalion in February 1953, and, in time for Easter, tins of chocolate biscuits.

As soon as the Durhams arrived in South Korea, local men were hired as porters. Second Lieutenant John Lightley remembered how useful they were:

Each Company had a number of Korean porters who endeared themselves to the Company by the great weight of supplies they could carry on the ‘A’ frames on their backs, and by their loyalty and good humour. They could carry in this manner considerable loads comprising boxes of ammunition, jerry cans of water and diesel, the latter for the heaters.

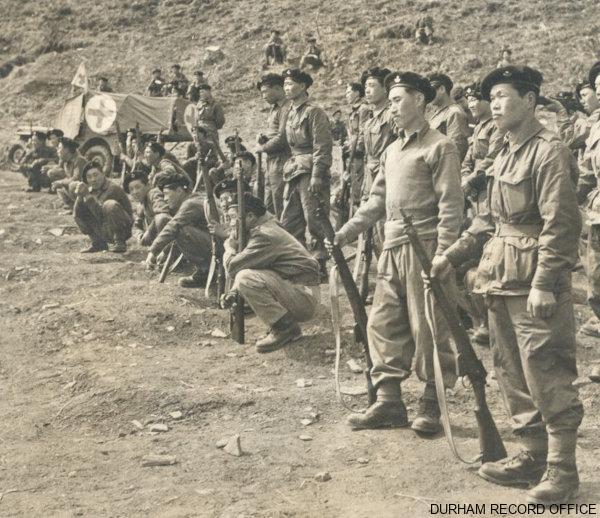

In March 1953, ninety-four trained South Korean soldiers joined the 1st Battalion DLI. Wearing the DLI cap badge and British Army uniforms, these KATCOM [Korean Augmentation Troops to Commonwealth Division] soldiers lived and worked with the Durhams and proved to be a valuable addition to the battalion. Two of these soldiers were killed before the ceasefire was called.

On 6 April 1953, after two months in reserve at Camp Casey, the 1st Battalion DLI took over Point 355 from US troops. Soon nicknamed ‘Little Gibraltar’, this steep hill overlooked a key crossing point of the Imjin River and had to be held despite the daily shells and mortar bombs and frequent night attacks.

One Chinese attack, starting from No Man’s Land close under Point 355, had previously almost captured the hill. Colonel Jeffreys was determined that his battalion would stop this from happening by sending out standing and ambush patrols to seize control of No Man’s Land. Then, towards the end of June 1953, the Chinese made a determined effort to take ‘Little Gibraltar’.

On 19 June, some twenty to thirty Chinese soldiers were surprised by an ambush patrol of Durhams, and, after a brief firefight, the enemy withdrew. Two nights later, an ambush patrol was itself surprised and two of the Durhams were wounded by grenades and one of the battalion’s KATCOM soldiers killed before the Durhams safely withdrew to their own lines.

The following night, Corporal Robert Lofthouse with three men was ordered to take up a position on a ridge to stop the main patrol from itself being ambushed. A twelve-man Chinese patrol was soon spotted by Corporal Lofthouse. The story of this ambush was later printed in the DLI’s Regimental Journal:

Corporal Lofthouse, showing great patience, waited for this party to bunch, which eventually they did. He then opened fire at short range and the stillness of the night was shattered by the chatter of the Brens and Stens and the ripping noise peculiar to the enemy burp gun. Every now and again the noise was punctuated by the sharper crack of exploding grenades. Half the enemy party was killed. The remainder fled down the hill. A larger group then assaulted the hill and, again, Corporal Lofthouse coolly engaged them and then withdrew off the hill to the main ambush position, closely followed by the enemy. Once Lofthouse’s party had re-joined the ambush… [the main patrol] opened heavy small arms fire on the enemy who dispersed having suffered heavy casualties.

For his bravery and leadership, Robert Lofthouse, who was wounded in the fighting, was awarded the Military Medal. In his eight months in Korea, he took part in twenty-eight patrols.

In the fighting that followed, during which the Chinese fired over 1,500 mortar bombs, one Durham soldier was killed and twenty wounded. But ‘Little Gibraltar’ remained firmly in the battalion’s hands.

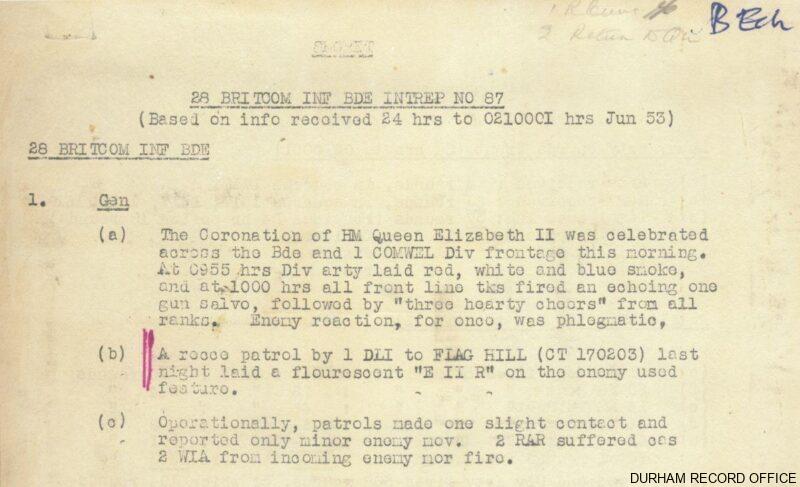

Whilst the Durhams were on Little Gibraltar, they celebrated Coronation Day, 3 June 1953. Captain Eric Burini later remembered:

‘A’ Company was in reserve beneath the main peak. On the night before, a patrol led by Lieutenant Bill Knott-Bower had gone across the valley to the Chinese positions and laid out some yellow and red fluorescent aircraft recognition panels in the form of ‘EIIR’ about ten metres in front of the Chinese forward trenches. So, the first thing we saw at daybreak were these panels that stood out brilliantly.

About half-way through the morning, every 25-pounder gun in the Commonwealth Division began firing red, white and blue smoke on the Chinese lines in front of us. While this was going on, the men in the forward positions jumped on to the trench parapets and gave three cheers for Her Majesty. There was some concern that the Chinese might take advantage of the cover provided by the smoke and attack us, but they behaved themselves and probably thought that we were all mad…

After last light, a searchlight was shone on our Regimental Flag flying from the flagpole and a group of our buglers played the Regimental calls grouped around the flag in full view of the Chinese, who once again did nothing – much to the relief of the buglers!

The Coronation of HM Queen Elizabeth II was celebrated across the Brigade and 1 Commonwealth Division frontage this morning. At 0955 hours Divisional artillery laid red, white and blue smoke, and at 1000 hours all front line tanks fired an echoing one gun salvo, followed by ‘three hearty cheers’ from all ranks. Enemy reaction, for once, was phlegmatic.

A recce patrol by 1 DLI to FLAG HILL (CT 170203) last night laid a fluorescent ‘EIIR’ on the enemy used feature.

Finally, after three years of war and months of peace negotiations, a ceasefire was declared in Korea at 10pm on 27 July 1953. The 1st Battalion DLI was then in reserve on the Kansas Line, living in tents rather than hoochies on ‘Little Gibraltar’. In his book ‘Looking for Trouble’ (page 80), General Sir Peter de la Billiere remembered that evening:

When the ceasefire at last came into effect on 27 July, we were having a dinner party in our mess tent, with candles on the tables and bottles of champagne: the instant the news arrived, we rushed outside and stood in awe, listening to the silence.

Before the Durhams left South Korea in September 1953, the battalion visited the UN Memorial Cemetery at Pusan to remember those who would not be returning home with them. After the memorial service, flowers were placed on each of the graves:

- 24 soldiers, who served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, were killed or died of wounds

- 3 were missing, presumed killed in action, as their bodies were never found

- 124 men were wounded, some with life-changing wounds.

During the battalion’s year in South Korea, those National Servicemen whose time was up had left on troopships for home and demobilisation. They were replaced by other National Servicemen sent out from England. But in September 1953 it was time for all the Durhams to leave Korea. The battalion, however, was not going back to England, but rather to Egypt and the Suez Canal. Only those National Servicemen who were close to their demobilisation day remained on board the troopship ‘Empire Orwell’ as it left Egypt for England.

Twenty-four soldiers who served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea were killed or died of wounds. And three men were missing, presumed killed in action, as their bodies were never found. In addition, 124 men were wounded.

1st Battalion DLI Roll of Honour, Korea 1952 to 1953

| Name | Date | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|

| Lance Corporal Edward O’Brien | 1 October 1952 | killed in action |

| Lance Corporal Ronald Douglas Carwood | 22 November 1952 | missing in action |

| Private Douglas Mervyn Bence | 22 November 1952 | missing in action |

| Private Dennis Ernest Baker | 22 November 1952 | killed in action |

| Private David Davies | 30 December 1952 | battle accident |

| Major Charles Patrick Donoghue MC | 2 January 1953 | killed in action |

| Colour Sergeant Joseph Graham Camby | 5 January 1953 | accident |

| Private John Alan Clements | 7 January 1953 | died of wounds |

| Private Dennis Reginald Cresswell | 20 January 1953 | battle accident |

| Private William Henry Thomas | 24 January 1953 | battle accident |

| Private Ronald Eacott | 27 January 1953 | killed in action |

| Corporal Hwang Po Koon, KATCOM | 11 April 1953 | killed in action |

| Lieutenant Edmond Lyons Willoughby Ratcliffe | 16 April 1953 | missing in action |

| Private Joseph Naisbitt | 27 April 1953 | killed in action |

| Lance Corporal Brian Bedford | 2 May 1953 | killed in action |

| Private John Wilfred Hall | 5 May 1953 | battle accident |

| Private James Eggett | 30 May 1953 | died of wounds |

| Private Donald Hargreaves | 30 May 1953 | killed in action |

| Sergeant Ralph Liddle | 5 June 1953 | killed in action |

| Private Samuel George Cotton | 8 June 1953 | killed in action |

| Major John Anthony Tresawna DSO | 10 or 11 June 1953 | killed in action |

| Second Lieutenant John Raymond Grubb | 16 June 1953 | died of wounds |

| Private Choung Si Ko, KATCOM | 22 June 1953 | killed in action |

| Private Ronald Cottingham | 23 or 24 June 1953 | killed in action |

| Private John Rowson | 11 July 1953 | killed in action |

| Private Barry Frank Gardiner | 17 July 1953 | killed in action |

| Private Peter Million | 17 July 1953 | died of wounds |